A personal story of sitting less and moving more by Connor Soles

Before coming to Queensland to study in the Doctor of Medicine program I considered myself an active person. I commuted by bicycle to my then-job as a medical scribe where I followed physicians into consultations and composed hospital charts on a mobile workstation. The hustle and bustle of the Emergency Department meant that I would cherish the rare moments that I would roll to a stop near the physicians alcove, cleverly positioned adjacent to the insta-coffee machine, and slump into a swivel chair to polish my notes. I had never experienced what it was like to be chained to a workstation seated, unmoving, for long periods of time before beginning medical school, and I’d never had to learn how not to be.

In my newly (half) furnished apartment (in Brisbane) I found that I could not escape our IKEA table turned desk, which was the only assembled piece of furniture aside from the couch. As a medical student studying now consumed and overwhelmed the majority of my waking hours, that and maintaining my relationship with my fiance who had accompanied me to Australia, left little time for my traditional workouts. I felt tethered to the stained canvas seat of our salvaged dining room chairs by the demand that I know everything. It wasn’t my view out the window that I struggled with. The natural wood grain of my impromptu desk caught the morning light that fell through the glass floor to ceiling doors of our third story balcony, which emerged into the branches of the trees bordering an old brick tenement. Our apartment stands between two of the steepest hills in Brisbane at the foot of what can generously be called a mountain. The view was spectacular, the endless sitting was not.

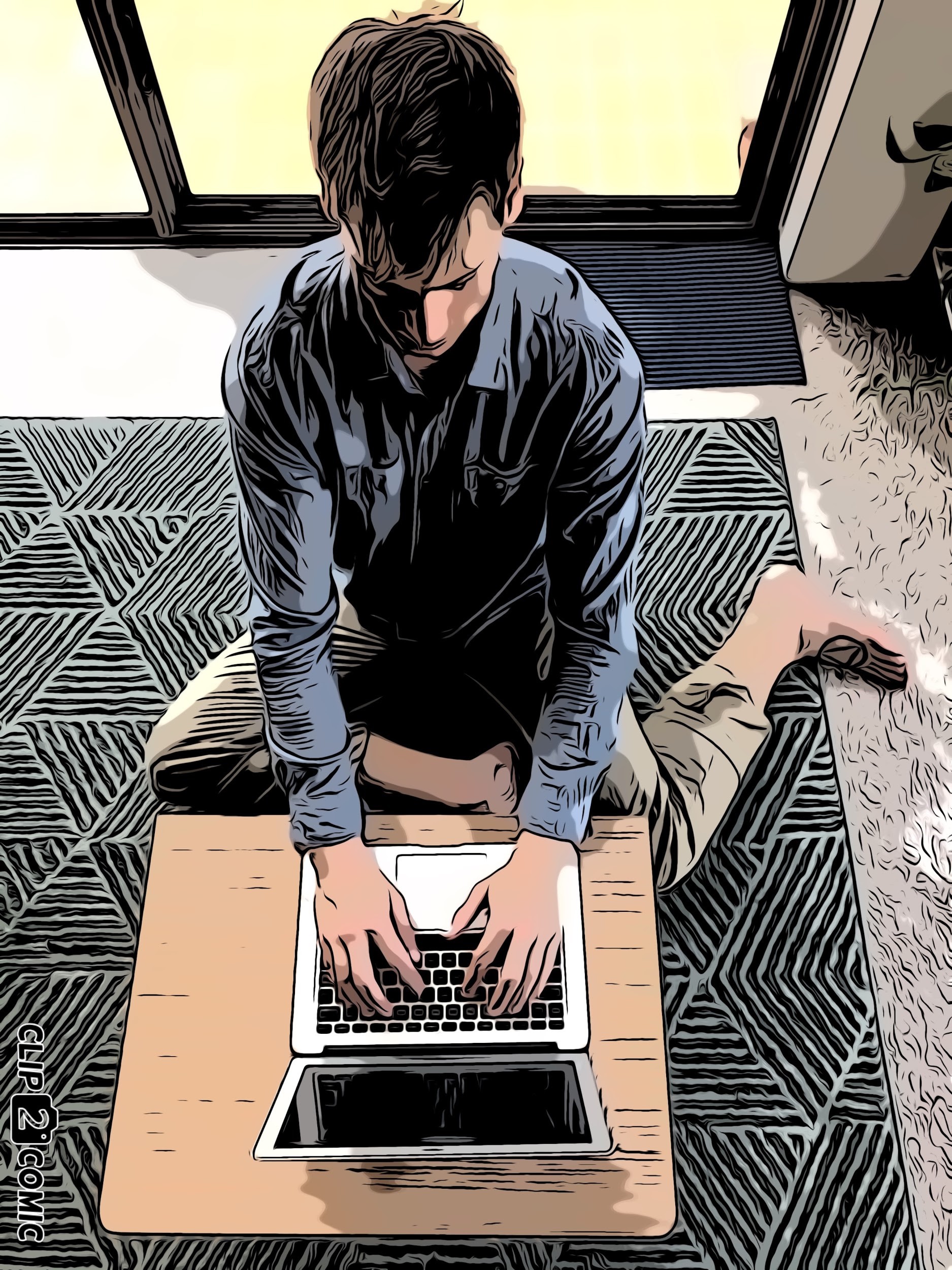

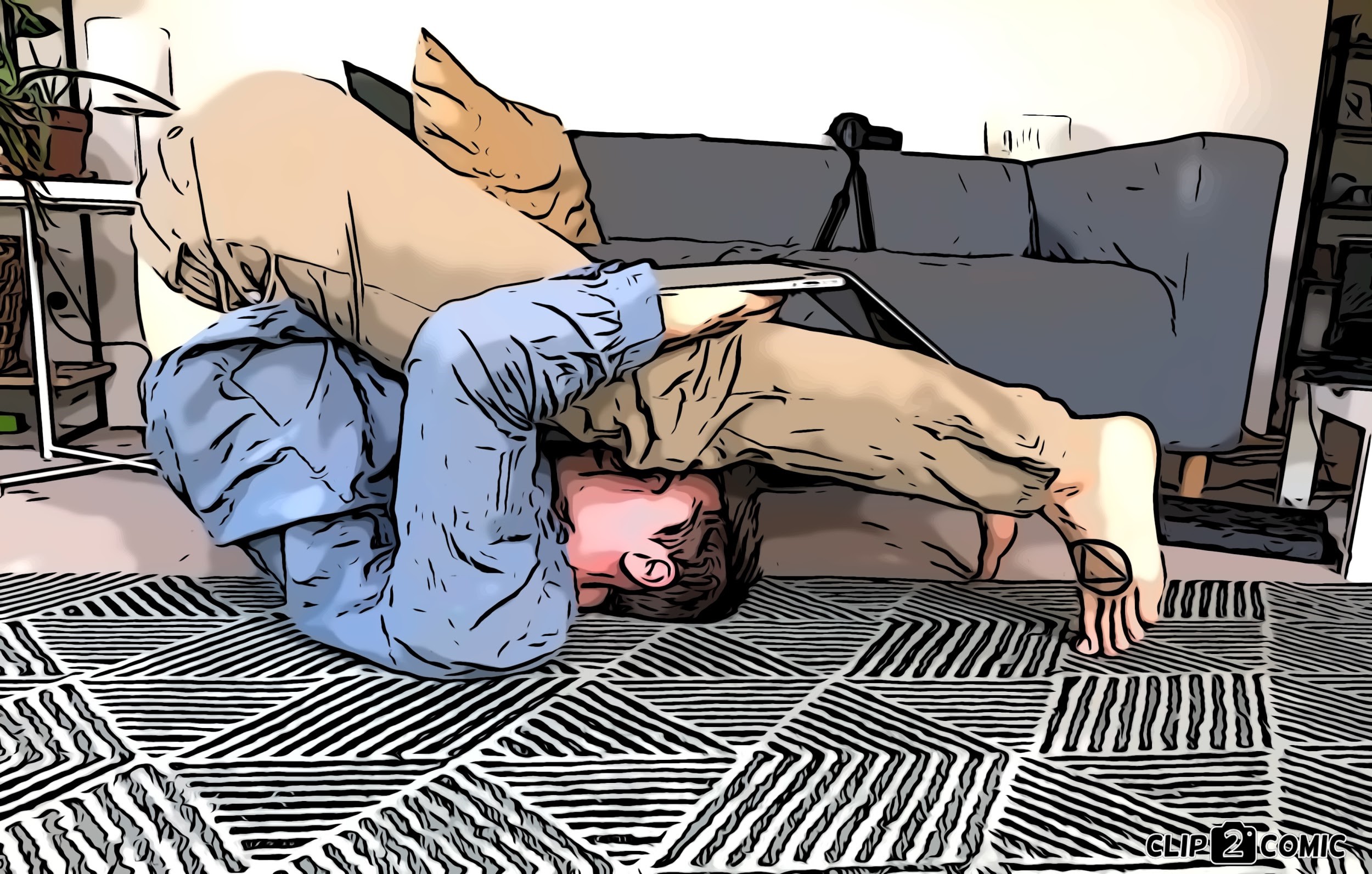

| Hours in this position lead to a stiff neck, weak kyphotic upper back, tight hip flexors, and weak lateral hips. |

I’m not here to advocate against any sitting ever, but when all you do is sit (as much as 11 hrs a day for some Australians)7 with bent legs, a rounded unengaged back, shoulders and head forward to stare into our computer screens as did when I started out as a new medical student our bodies change to accomodate a lack of activity that evolution never prepared us to be able to cope with.

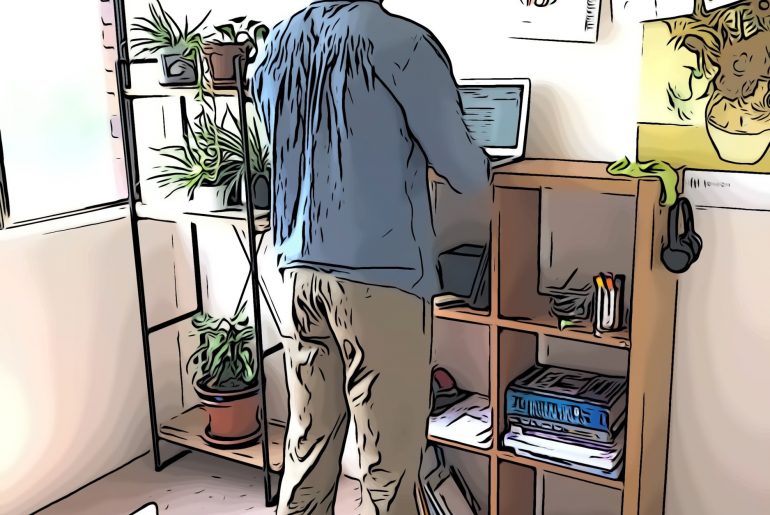

Fast forward to today, about to start my second year of medical school and I am writing this from the standing desk in my office.

| Here in my study room, the floor littered with lacrosse balls, exercise bands, and filled with some of the hardest to kill plants on the planet earth, I feel refreshed and alert. |

My schoolwork has not decreased and continues to take up the majority of my time, the difference between then and now is a set of tips and tricks that I have learned and will attempt to show in this article to “stack” movement back into my life.

Sitting is ubiquitous and seemingly inescapable in western society. Our dominant mode of exercise consists of moderate to heavily taxing movement known as “the gym.” The gym, contrary to popular association is not the pinnacle of scientific advancement in health research distilling the necessary cardiometabolic benefits into a convenient package, but the false equivalence between quantity of movement and it’s quality and temporality. In my most fanciful imagination I dream of the expanding savannahs of our predecessors H.erectus and H. Habilis dotted with Anytime Fitness franchises advertising “get fit for your day of foraging.” This of course is humorous in its absurdity. For 3-4 million years our ancestors’ environment shaped their bodies. Our bodies, a collection of cells, are adaptable and adapt to what we do. It is intuitive that our habits change our bodies in the same way that we assume a gymnast can touch their toes or how an olympic powerlifter may struggle to find clothing large enough to contain their bulging frame. Our own genome in its present form is estimated to be merely 1000 generations old (40,000 yrs), an evolutionary “eyeblink” and no time at all to have adapted to the vastly different way of living we have developed just within the last 2000 years.5

Our movement or lack thereof has consequences. Evolutionary anthropologists describe the consequences as the rise of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease (CVD) and diabetes. Study of contemporary hunter gatherer peoples provides us with a contrast to our current mode of living. Among hunter gatherer populations non-communicable disease accounts for <10% of mortality past the age of 60. And while infection inflicts the greatest burden of disease for those who reach the age of 45 the average life expectancy is nearly par with many contemporary societies (72 y.o compared to 75 y.o.). The two most notable differences that account for the differences in health outcomes are lack of access to processed highly calorie dense nutrient poor food, and a drastically different movement profile.6 For example the Hazda people were found to exert themselves between 6-9 hrs per day walking between 9.5-14 km. The 8 hours we spend at our desk jobs in addition to sometimes lengthy commutes provide a stark contrast.1 It surprised me that among hunter gatherer peoples the level of activity as measured by accelerometry persisted past the age of 60.6 Even when compared to what could be considered our recent agricultural past in contemporary Amish, studied communities took an average of 18,000 steps to our mere ~6000.1 These drastic changes have consequences.

The body of research is growing on mortality, cardiovascular risk, and diabetes related to increasing time spent sitting.1,3,4 “Yeah, yeah,” you might say dismissively, “We all know that we shouldn’t be sitting so much.” But what’s the big deal, right? The current recommendations aim towards ~30 minutes of physical activity a day (150 min/week) of which only 10% of us actually achieve.1,6 The big deal is that new research has emerged indicating a daily workout does not mitigate the effects of prolonged sitting. A paper in the Journal of Sports Sciences examined participants subjected to prolonged sitting (between 6-8 hrs) with subsequent exercise. Cardiometabolic risk factors were measured using mean arterial pressure (MAP), postprandial blood glucose, and blood velocity through the posterior tibial artery (low flow in which is correlated with increased risk of CV complications). An acute dose (~60 minutes) of exercise following prolonged sitting failed to reverse the decline in posterior tibial artery velocity that developed during time spent sitting or reverse changes in blood glucose response, and MAP.2 The researchers noted that sitting decreased the return of blood to the heart, causing the heart to work harder. This strain on the heart was captured in elevated MAP values. This may be better understood through studies of rodents among whom prolonged inactivity altered the expression of ~27 genes which persisted long after they began to move again (~4 hrs).1 This may leave some feeling hopeless but do not despair! Though we may not redeem ourselves on the elliptical machines languishing in the fluorescent halls of our local fitness establishments we may find that the answer was right in front of us all along.

A recent meta analysis from the Journal of Sports Medicine (2018) on metabolic markers of health showed that frequent light to moderate movement breaks interrupting periods of sitting can limit many of the health complications of our otherwise sedentary occupations. A major focus of the study was examining the effects of movement breaks on insulin and glucose levels due to their high association with morbidity and mortality. Surprisingly the reductions in postprandial blood glucose were consistent across a broad range of body types (as measured by BMI). Duration of breaks were recommended to exceed 10 minutes, evidence is poor for breaks of less than 10 minutes.

The research listed above around how breaking up time sitting improves health and wellbeing also has implications for productivity. Specifically reducing “presenteeism.” Presenteeism is lost workplace productivity due to distraction and disengagement. A health intervention in 6 of Spain’s universities found that introducing a “sit less move more” program consisting of a step challenge that equipped employees with pedometers, resulted in greater engagement at work and reduced productivity loss.7 This study and others like it are the basis for national “move more, sit less” movements. Organizations like Australia’s own BeUpstanding partner with businesses to create plans integrating movement into the workday.

In light of the available research I can now understand that while I exerted myself commuting several miles by bicycle to my morning lectures, after a day of sitting and studying I still felt, for lack of a better word, bad. My shoulders constantly ached, I felt tired, and the physical stress was putting a strain on my relationship. I knew that something had to change, but I felt as if the demands on my time left little room for flexibility. I remember thinking, “if I only didn’t have to do [insert chore/task] then I would have time to go for a run.” I felt like I was racing to tick boxes off of a never ending list so that I could finally move my body.

I was desperate to introduce movement into any facet of my life. I started to think about my chair like a cast or a surgical brace that I needed to escape. It goes without saying that ergonomics has given us some of the most comfortable chairs on the planet. Hands down. When I sat to study in my office chair I was so well supported that the only effort I had to exert was when I sat down or stood up, by being more comfortable I succeeded only in moving even less. Fortunately this conundrum occured around the time that Australians in Brisbane chucked/tossed/binned all of their unwanted furniture and detritus onto the side of the road. That is where I found my first sitting desk. To use dogs for comparison a sitting desk is like a dachshund, normal sized body but teeny little legs, that enables one to sit on the floor .

| When I sit on the floor to use my desk I am less comfortable but it doesn’t make me tired. If anything it wakes me up. |

When I first started studying with the sitting desk (whose previous purpose I am relatively certain was to serve as a plant stand) I found I had trouble sitting upright. The effort of engaging my core and remembering to stay upright made me more alert. Without the chair seat to cushion my rear I had to adjust how I was sitting frequently, yet more movement.

Having to get up from the floor is a full body exercise, especially engaging the gluteus maximus, which doesn’t have to do much work rising from a traditional chair. Just go ahead and try it while you’re reading this article. For many of us, transitioning to floor sitting may come as a challenge. For those not sure where to begin I found this podcast by Katy Bowman helpful.

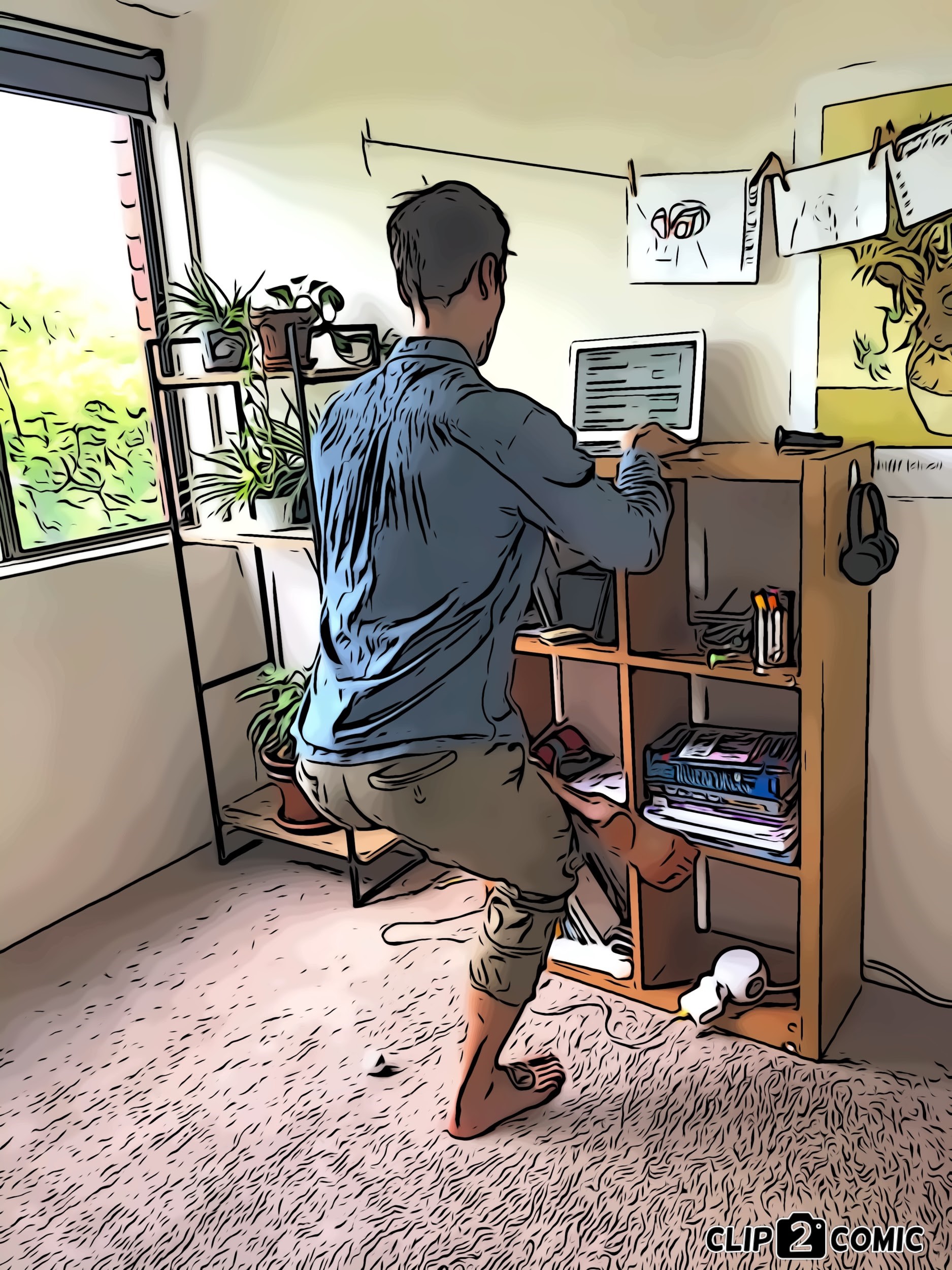

But sitting at a sitting desk, even engaging my core and sitting in new ways became tiring after several hours. Queensland had us covered though! Our next curbside find was a 6 cube organiser IKEA tv stand that when flipped on edge became the perfect height standing desk! It is mostly stable…

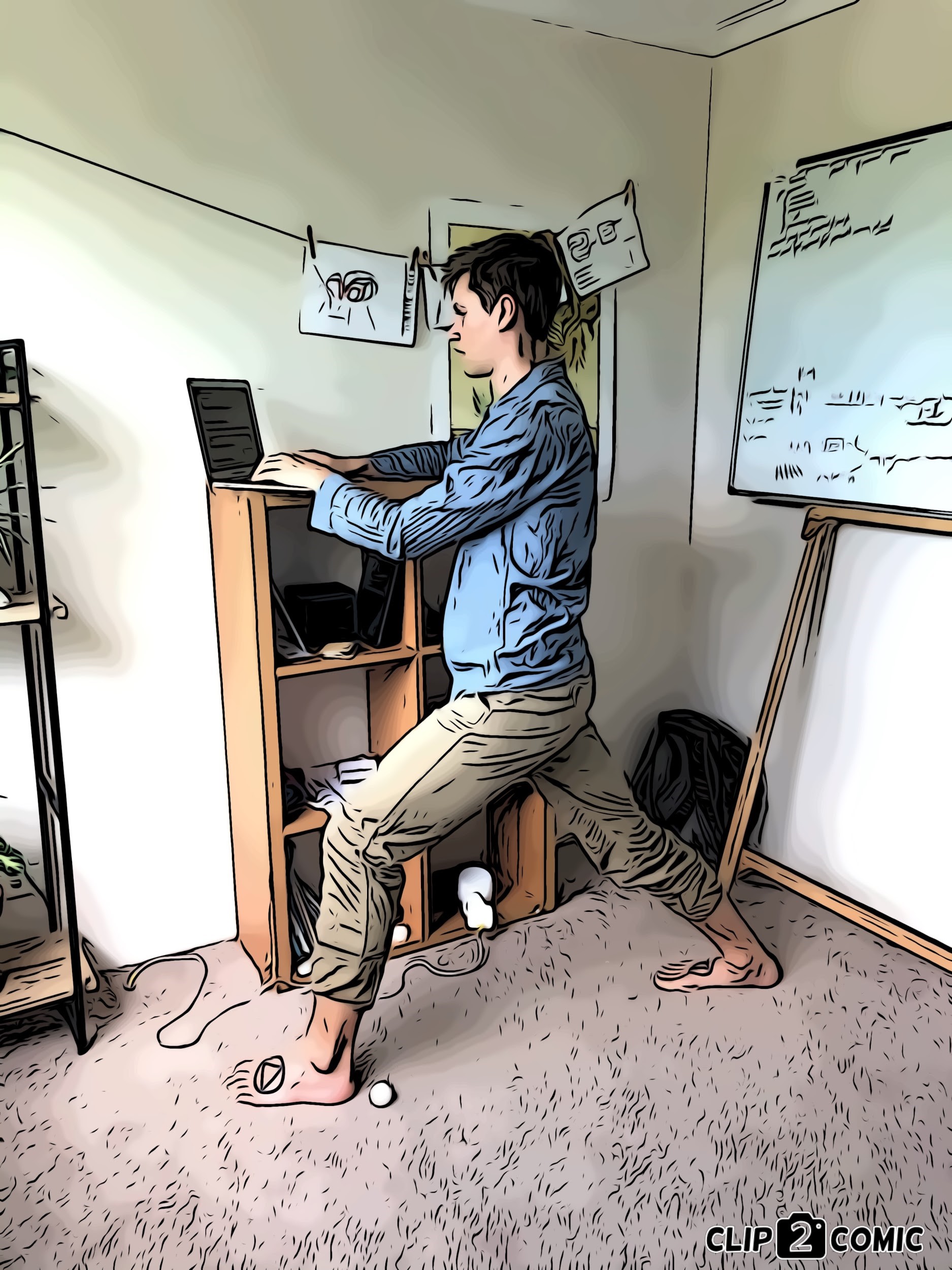

| Below are a few more ways to work at a standing desk (Clockwise from top): In a lunge position at an angle to my desk, in a squat with my leg over my knee, and in the tree pose that I use most often because I remain at the same height relative to my desk. |

| Working from one leg or in a lunge allows me to work on my balance and load in a way other than standing. |

I spent several months moving between the sitting and standing desks as I eased into school before my partner suggested some new ways to move.

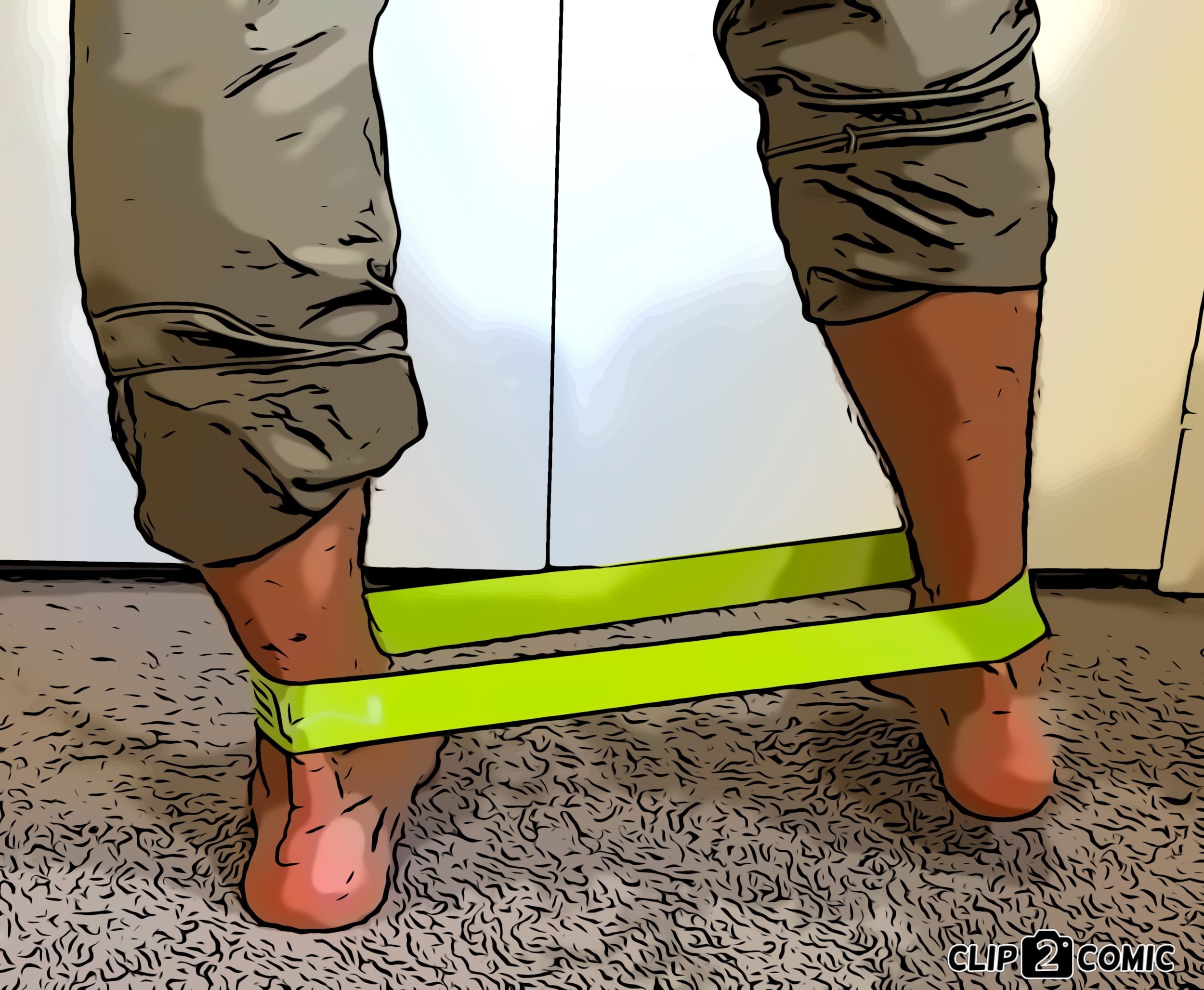

| Ways I engage my feet while at my standing desk (counter-clockwise from top):

(left) A Yamuna hedgehog Is a challenging surface that stimulates my feet while I type. I have a variety of exercise bands to use my stabiliser muscles. A half dome that I balance on to engage my core and my mind while I work. (bottom) Rolling a lacrosse ball takes the small joints of my foot through their full range of motion. |

| (below) The struggle of maintaining this position can certainly make work more entertaining, which is why this is definitely my move of last resort after too much study. |

Lately I go for walks every morning at sunrise with my fiance. I don’t really care to wake up early but It is the only time of day when the Queensland sun is tolerable. I am fortunate that my apartment is situated a block away from two city parks where we most often go. The parks are popular at any time of day but with the quiet couples and walkers strolling in the morning light it is quite peaceful. The usage of the parks in the dense city has provided an equal abundance of litter and the last and most recent way in which I stack my life. When we walk in the mornings we take a plastic bag to fill with trash. I’m still finding new ways to sit less and move more but now that I’ve made the transition I wouldn’t ever go back.

This blog was written by Connor Soles as part of his placement from the Faculty of Medicine, UQ

References:

- Katzmarzyk, P.T., 2010. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and health: paradigm paralysis or paradigm shift? Diabetes, 59(11), pp.2717–27125.

- Younger, Amanda M et al., 2016. Acute moderate exercise does not attenuate cardiometabolic function associated with a bout of prolonged sitting. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(7), pp.658–663.

- Owen, N., Salmon, J., Koohsari, M. J., Turrell, G., & Giles-Corti, B. (2014). Sedentary behaviour and health: Mapping environmental and social contexts to underpin chronic disease prevention. British Journal of Sports Medicine

- Saunders, T. et al., 2018. The Acute Metabolic and Vascular Impact of Interrupting Prolonged Sitting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 48(10), pp.2347–2366.

- Stone, J.A. & Stone, J.E., 2016. Aboriginal vascular health and insights into atherosclerosis. Journal of Human Hypertension, 30(4), pp.223–224.

- Pontzer, H., Wood, B.M. & Raichlen, D.A., 2018. Hunter‐gatherers as models in public health. Obesity Reviews, 19(S1), pp.24–35.

- Puig – Ribera, A et al., 2017. Impact of a workplace ‘sit less, move more’ program on efficiency-related outcomes of office employees. , 17(1), p.455.

Comments are closed.